“Those that fail to learn from history, are doomed to repeat it.”

Archivist Note: This blog was originally written by our Archives Technician, Matthew Cook on 26 November, 2021 just days before another atmospheric river would cause further flooding and highway closures in B.C. Maybe it’s time we start looking at our past challenges and mistakes as we rebuild towards the future.

On November 2021, denizens of the Lower Mainland experienced a series of catastrophic floods, which led to the destruction of countless houses, especially in the Sumas Prairie region, and the shut down of highways, cutting off people from work and family. Premier John Horgan commented on the floods, stating that “Even the experts were just completely surprised by it,” and “I think all British Columbians fully understand that now we have to better prepare for events like this. But we couldn’t have even imagined it six months ago” (Hoekstra 2021). Contrary to the premier’s comments, this isn’t the first time that the Fraser Valley has experienced such catastrophic flooding. In fact, events of this magnitude have occurred several times in the not-so-distant past, notably one in 1894, one in 1935, and the other in 1948. The following blogpost will explore the impacts of these previous floods, and determine what we may or may not have learned from them in order to prepare ourselves for the November 2021 Pacific Northwest Floods, and floods in the future.

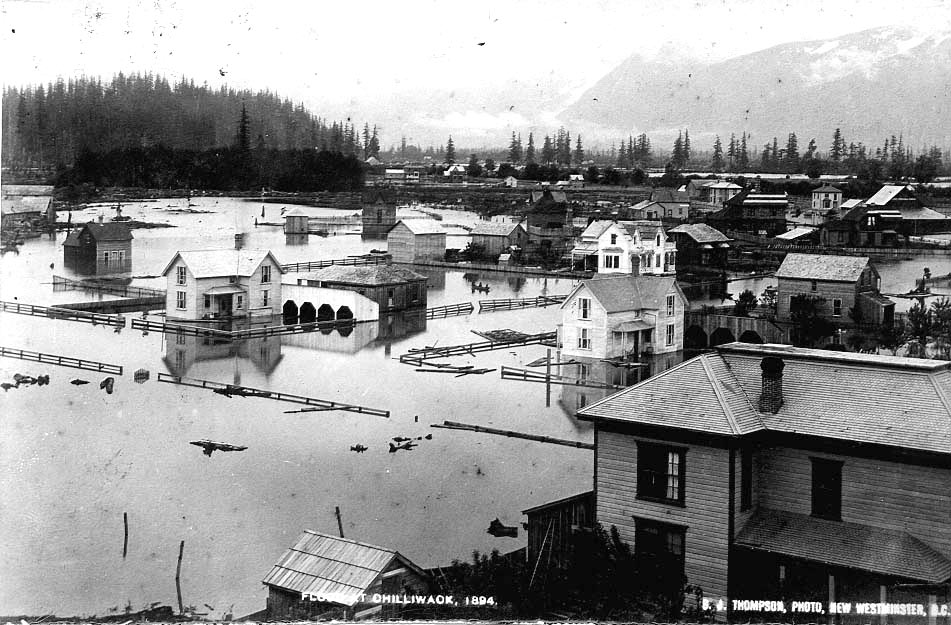

The first major flood experienced by European re-settlers in the area came in 1894. According to the Chilliwack Museum and Archives, flood waters from rapid snowmelt reached a level of 7.85 meters on the Mission gauge – a foot higher that the 1948 flood. Prior to 1894, there had been no flood control measures except for a dam built across the Hope Slough at Rosedale in 1892. Neither the Province nor the Township could raise much funding for dyking, although a few farmers had attempted to dyke their own lands. This resulted in almost the entirety of the Chilliwack community being submerged in water, along with extensive damage to crops and livestock (see photo 000691). “The streets of Chilliwack became streams that were only passable by boat or raft. Boys provided ferry service for those needing to cross the streets with their homemade rafts.” After the 1894 flood, a proper dyking system was constructed throughout the Fraser Valley. However, in the ensuing decades many of the dykes, such as the one at Matsqui, were allowed to fall into disrepair (Chilliwack Progress 1930).

The Chilliwack region was tested again in 1935, when the subsequent melting of ice brought about by a devastating ice storm raised the water levels to dangerous heights (see photo 2012.061.034). The City of Chilliwack had largely avoided major floods, but the Sumas Prairie, which 11 years earlier had been the Sumas Lake prior to it being drained for a land reclamation project, would experience up to 10 to 15 feet of substantial runoff. Barns, homes and other buildings were damaged or ruined, and many farm animals situated on the reclaimed Sumas Prairie were drowned (Chilliwack History Perspectives 2016).

![Flood Near Chilliwack Mountain, ca. 1935 [2012.061.034]](https://www.chilliwackmuseum.ca/wp-content/uploads/sites/4/2021/12/2012.061.034.jpg)

In 1948 the floods returned, and the high-water mark at Mission rose to 7.5 meters. While lower than the 1894 flood, the torrent of water broke the neglected dykes at Agassiz, Chilliwack, Nicomen Island, Glen Valley and Matsqui, rushing in to a now highly populated and developed region. The floodwaters shut down two transcontinental rail lines; submerged part of the Trans-Canada Highway, and forced the evacuation of 16,000 people. In all, 2,300 homes were damaged or destroyed, and causing millions of dollars in damage. (see 2013.123.013).

The floods of 1894, 1935, and 1948 forewarned those living in the Fraser Valley that flooding was a very real hazard. In 2007 Delta mayor Lois Jackson issued a warning, stating that “There’s going to be hell to pay if that river floods,” and “It’s an absolute disgrace that nothing has been done,” (Soltau 2021). This sentiment was supported by the Chilliwack MLA at the time, asserting “We have to take the position that flooding is not an option,” and “our first obligation is to do everything we possibly can to prevent it” (Soltau 2021). This was all in response to federal and provincial governments ceasing their funding of dyke work in 1995. Even by 2018, B.C.’s auditor-general, Carol Bellringer reported that the provincial government “may not be able to manage flood risks given a number of factors including a lack of staffing and technical capacity, outdated flood-plain maps, and roles and responsibilities that are spread out across many agencies and levels of government” (Hunter 2021).

Then, 73 years after the 1948 Flood, the November 2021 Pacific Northwest Floods occurred. Brought about by a record-breaking amount of rainfall, the dykes were breached by river water, which overflowed into the Sumas Prairie, shutting down major highways, displacing thousands of residents, and causing millions of dollars worth of infrastructural damage and loss to livestock. History had seemingly repeated itself, and while some people had the foresight to warn the province how dykes and other protective measures had failed due to being neglected in the past, we still found ourselves woefully unprepared.

Concerning Premier John Horgan’s comment on the November flood, stating that “we couldn’t have even imagined it six months ago”, history has shown that living in the beautiful Fraser Valley comes with its risks—floods being foremost amongst them. The First Nations communities understood this, with the Stó:lō people sharing stories of ancient floods that far surpassed the 1894 Flood (Luymes 2021). At the end of the day, we all want to forget about the hardships of the past as we look towards the future, but the Fraser Valley demands our vigilance, and as the popular saying goes: “Those that fail to learn from history, are doomed to repeat it.”

Works Cited

Chilliwack History Perspectives. 2016. “CHILLIWACK’s TWO DEVASTATING ICE STORMS (1917 and 1935)”. Facebook. https://www.facebook.com/chilliwackhistory/posts/chilliwacks-two-devastating-ice-storms-1917-and-1935-during-the-first-half-of-th/1797849167159876/

Chilliwack Progress. 1930. ‘Associated Boards Ask Dyke Protection, Road Improvement’. https://theprogress.newspapers.com/image/43938199/?terms=dyke&match=1

Hoekstra, Gordon. 2021. “’Couldn’t have Imagined it Six Months Ago’ says Horgan, but scientists have been issuing climate warnings for decades’ Vancouver Sun.

Hunter, Justine. 2021 “BC Floods: The Province had been warned natural disasters would hit more often, and it was not prepared. The Globe and Mail.

Luymes, Glenda. 2021. “From the Archives: The 1894 and 1948 Fraser Valley floods”. The Vancouver Sun

Soltau, Carolyn. 2021. “From the Archives, 2007: Fear on the Fraser – Inside BCs Big Flood Threat.” The Province.

Comments are closed.