Written by Matthew Cook

Please see the bottom of the post regarding an update on the violin!

Processing donations has always been one of my favorite tasks in the Archives. There is something so satisfying about bringing structure and order to the many piles of papers and photographs that make up the endless backlog. That alone makes the effort worthwhile, but sometimes a donation comes around that really peaks my interest, and fuels my desire to investigate further.

Enter the land deed for George Washington Chadsey from 1902 (ID 2023.013.001). For those unknowing, Mr. Chadsey was one of the earliest European settlers in the Chilliwack region. He arrived at Sumas in 1866, where he pre-empted[1] District Lot 87. He raised six children and spent most of his time farming. Eventually he and his family moved to Chilliwack proper in 1902. He then spent the rest of his life as a town clerk, tax collector, and later magistrate in the county court.

However, it’s not George Washington Chadsey’s status as an early European settler of Chilliwack that caught my attention. It’s that while doing research on his land deed, I discovered that he was also renowned for having a very special violin.

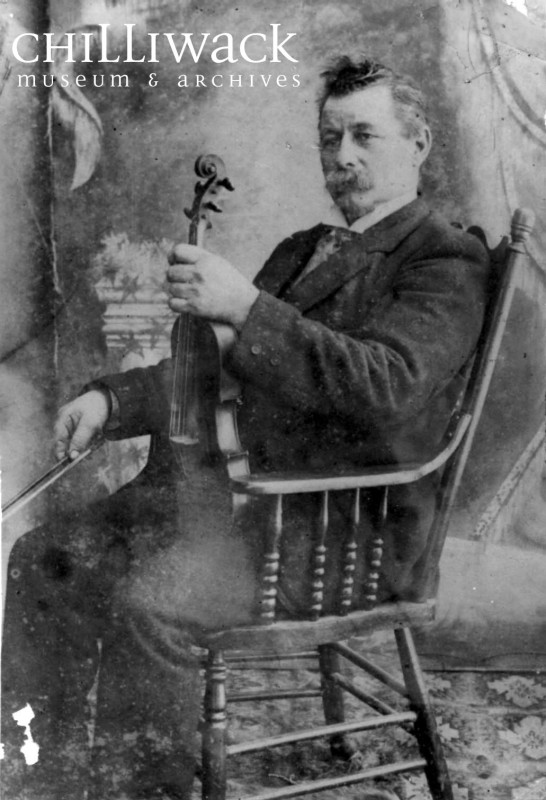

Let me elaborate: Once upon a time in the 1860s, George Chadsey found himself at a hotel in the Cariboo region. There he chanced upon a violin, and as he played a few notes, he realized that it bore a particular richness in tone that only instruments of the finest make possessed. The hotel keeper confirmed Mr. Chadsey suspicions, informing him that the violin was in fact made by none other than Antonio Stradivari, an Italian luthier and craftsman of the famous Cremona school. Mr. Chadsey looked over the violin, and indeed found the maker’s name and date, 1694, engraved on the instrument. When pressed further, the hotel keeper stated that he came into possession of the violin from a wandering Italian, who pawned it for $50.00 (well over $2,500 dollars in 2023), before meeting an untimely end at one of the nearby gold mines. That was all Mr. Chadsey needed to be convinced that he had a real treasure on his hands, and after a brief period of bargaining, he purchased the violin from the hotel keeper for $30.00. Ever since then, the two had been inseparable. Mr. Chadsey had the instrument refurbished, and would often be heard playing it during concerts at Henderson Hall. He had many chances to sell the violin for a pretty penny, but never did, and was still in possession of it until his death in 1910. After that, the Stradivarius violin seemingly just disappeared, becoming lost to time, according to Kelly Harms. Indeed, it seemed to have become “Just one of many tantalizing Chilliwack mysteries” the former archivist wrote conclusively. (The Chilliwack Story 2007, p.15).

This did not sit right with me. Kelly Harms wrote that article on George Chadsey and his violin back in 2007. Surely between then and 2023, more information had made its way into the archives to help trace its whereabouts. Luckily, after an afternoon of meticulously sifting through the stacks, I had a breakthrough in the form of a single piece of paper from the Marie Wheeden fonds (ID 2004.052.0085) stating that Mrs. Marjorie Fetterley (nee Chadsey), the granddaughter of George Chadsey, had come into possession of the violin. This piece of information fits the puzzle, as my research (ID AM 0713) revealed that Majorie Fetterley’s father, Edmund Chadsey, was fond of his father’s violin and would often play it. Therefore, it would not be too farfetched to ascertain that the violin was passed to Edmund after George’s death, and then to Marjorie upon Edmund’s passing.

Unfortunately, Marjorie Fetterley herself passed away in 1978, and after that the trail goes cold again. But I wasn’t ready to call it quits quite yet. As it so happened, one of the volunteers at the archives is an acquaintance of the Fetterley family. Through this volunteer, I was able to learn that a grandchild of Marjorie Fetterley was familiar with the violin, but currently did not know of its whereabouts, although they were willing to investigate further.

So that is currently where my investigation has led me, which all started with the donation of George Chadsey’s land deed. This was a research opportunity that came about rather spontaneously, but I nevertheless found it to be both compelling and rewarding. As it turns out, similar scenarios occur almost regularly here at the Chilliwack Archives. More often than not, a visitor will come in with a hazy memory or question about Chilliwack’s past, and using the Archives’ ever-growing resources, we help illuminate those murky areas, and connect them to the present. With that said, should you have any inquiries concerning one of the many tantalizing mysteries of Chilliwack’s history, please pay us a visit. We will be more than happy to help you with your research!

Update – September 27, 2023:

Thanks in no small part to one of our volunteers, I was able to connect with a relative of Marjorie Fetterley, who kindly provided me with additional information about the whereabouts, and nature of George Chadsey’s famous violin. According to the relative, Marjorie Fetterley likely gave the violin to one of her granddaughters, Verna De Armond (nee Fetterley), upon her passing. Again though, the plot thickens, as Verna herself passed away in 1984, and the relative suspects that the violin was then inherited by one of her children.

Additionally, Marjorie Fetterley apparently had the violin appraised, and it was determined, unfortunately, not to be an authentic Stradivarius. Still though, the instrument has a rich and compelling story to it, and remains an important heirloom to the Chadsey family’s descendants, and to the community of Chilliwack as a whole.

[1] Kate Feltren, the Curator here at the Chilliwack Museum and Archives, provides an explanation for what pre-emption means: “Pre-emption was the process of acquiring land that had not yet been surveyed by colonial governments for agricultural use.” Today, much of the Fraser Valley is designated as Agricultural Land Reserves due to these pre-emptions, which brought about not only rapid urbanization, but also a disruptive shift in the traditional Stó:lō way of life from being based around water channels to agricultural productivity.

Comments are closed.